11.2. Classes¶

The objects we’ve seen and used thus far have all had specific types, and any given object type has a consistent definition across all objects of that type. Every DataFrame contains the same set of methods and attributes, every String object works the same way, and every File object can be used just like any other. The consistent set of functionality within an object of a given type must be defined somewhere. That’s where classes come in.

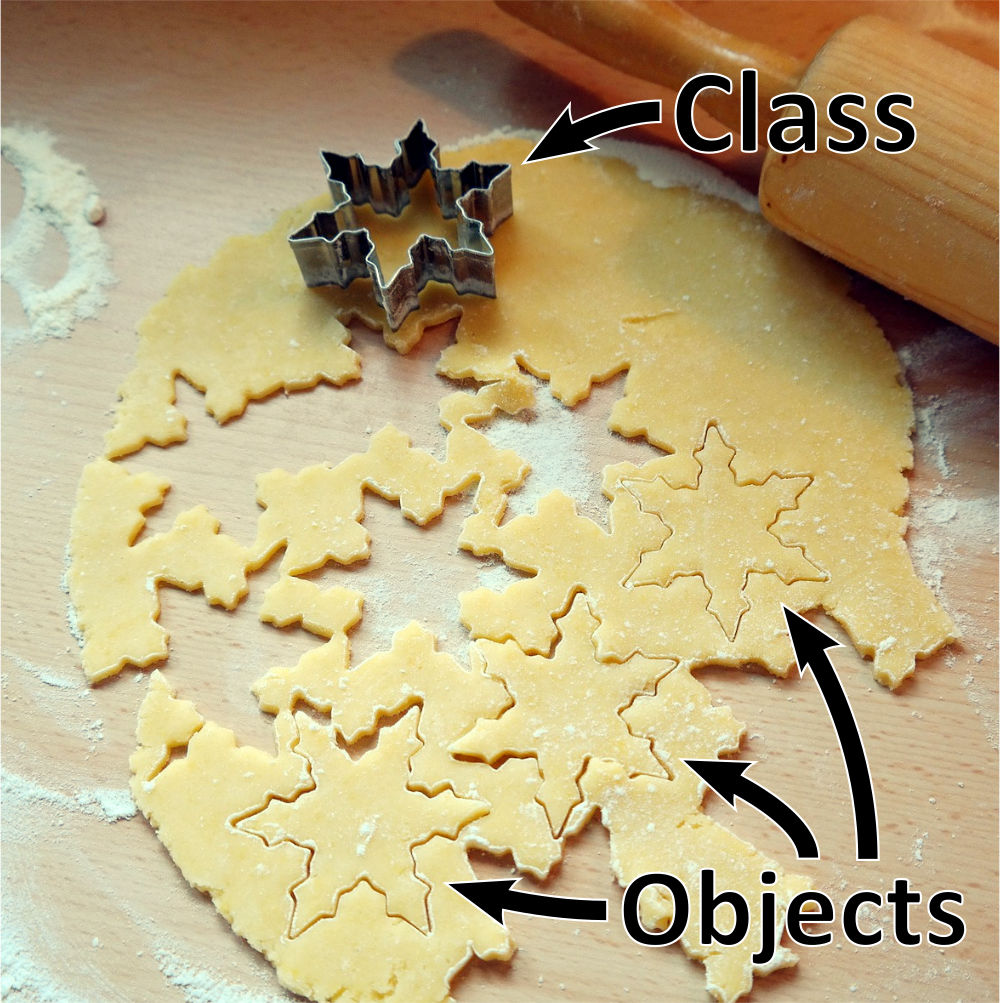

A class defines a type of object. It specifies what attributes any object of that type will have and what methods it will have. A common analogy is to think of classes like cookie cutters and objects like cookies made from them. Each cookie cutter defines the shape of a particular kind of cookie, and it can be used to make one cookie or many cookies with that shape.

Cookie cutter and cookies¶

We often call each object created from a given class an instance of that

class, sometimes referring to the variables that hold those objects as “instance

variables.” For example, if df is a DataFrame object, we could also say that

df is an instance of the DataFrame class.

11.2.1. Defining a Class¶

As with everything else in Python, the definition of a class must follow a particular syntax:

Syntax Pattern

A class definition has the form:

class <class name>:

<body>

By convention, class names are typically capitalized. This helps us differentiate class names from variable and function names, which are typically not capitalized.

The <body> can contain one or more method definitions:

def <method name>(self, <optionally more parameters>):

<body>

A method definition is like any other function definition, but every

method must have at least one parameter, and that first parameter is

conventionally named self. [This isn’t an absolute rule, but it will

always be followed as far as we are concerned in this book.]

Let’s look at an example. Try running the following with CodeLens. It won’t print anything out, but it will create the class.

This defines a class named Box (capitalized, as noted above) with two

methods: __init__() and draw(). Notice that both method definitions

are indented inside the class. This puts them inside the body of the class

definition. If one were not indented, it would just be a normal function

definition, no longer part of the class. (Try editing the code to remove

the indentation of draw and see what changes when you re-run it.)

When this code is executed, it creates the class, but none of the instructions in its methods are executed (try it!). Class definitions are similar to function definitions in this way; executing a function definition creates the function, but it doesn’t run the function’s body until it is called.

11.2.2. Instantiating a Class¶

To create an object from a class, we call its constructor function. The constructor is a function with the same name as the class that is created implicitly when we define the class (that is, you do not have to define a function with the same name as the class yourself). The constructor returns a new object of the class’s type that can then be stored in a variable or otherwise used in an expression. This is also called instantiating the class, because we are creating an instance of it.

The above code is best explored using the CodeLens tool. Upon executing the

first line, the class definition is created (you can see that it contains the

two methods defined in it). The next line, a = Box(6, 4), is calling the

constructor for the class, a function with the class’s name. Upon executing

this line, you can see that the flow of execution jumps into the __init__()

method.

The __init__() method

When a class is instantiated in Python, the interpreter will automatically

look for and call a method named __init__() in the class, if one exists.

The name itself is thus special; if the method is named anything else, it

will no longer be called automatically in that situation.

The goal of the __init__() method is to initialize the newly-created

object’s attributes (the data stored inside the object). Attributes are

created and assigned using dot notation with the self parameter.

The self parameter

The first parameter of a class method, typically named self, is

automatically assigned a reference to the particular object in which a

method is running. This gives the method access to the attributes and

methods of that object.

If the first parameter of the method is not named self, it will still be

automatically assigned a reference to the same object. We almost always

call it self because it is descriptive of what the variable references,

and the convention makes it easier to read and understand code.

Watch in CodeLens as __init__() is called. The method is defined with

three parameters, self, width, and height, but it is called with

just two arguments, 6 and 4. The first argument, self is

automatically assigned a reference to a new Box instance, while width

and height get the two arguments from the function call.

With self referring to a new Box instance, self.w and self.h are then

two attributes, named w and h, of that instance. The two assignments

in the __init__() method create them and give them values.

Note

This is a common pattern for __init__() methods in classes. Often, you

want to be able to give initial values to an object’s attributes when you

create the object. Each attribute you want to initialize in this way can be

given a parameter in the __init__() method, and then the method can

create attributes and assign them values given to the constructor as

arugments. For example:

class Example:

def __init__(self, param1, param2, param3):

self.attr1 = param1

self.attr2 = param2

self.attr3 = param3

new_object = Example(123, "Hello", 0.5)

When __init__() returns, you can see that the newly-created Box object,

the return value of the constructor, is then assigned to the variable a.

Finally, the code calls a.draw(), and the flow of execution moves into the

draw() method. Again, the first parameter, self, is assigned a

reference to the object in which the method is being called. Inside the method,

using dot notation with the self parameter allows it to access the object’s

attributes, in this case using them to control the width and height of a

printed box.

11.2.3. One Method, Multiple Instances¶

To reinforce the idea that self will always be a reference to the

particular object in which a method is being called, look at the following code

in CodeLens.

Each time __init__() is called, its self parameter is referencing a

new object. And each time draw() is called, its self parameter

references just the particular object in which draw() was called. Another

way of thinking about it is that for a method called via dot notation, self

will be a reference to the object on the left side of the dot.

11.2.4. Fruitful Methods and Void Methods¶

In the chapter on Functions, we discussed two types of functions in

Fruitful Functions and Void Functions. The same distinction can be applied to a class’s

methods as well. The draw() method above is a void method, because it

doesn’t return a value. We can define fruitful methods that return values as

well. For example:

Here, the get_area() method is a fruitful method with a return statement.

When it is called, the method returns a value, which here we save in a new

variable.

Note

It can be helpful to think of void methods as things an object can do, and when you call a void method, you are telling an object to do that thing. Fruitful methods, on the other hand, can be thought of as answering a question, and when you call a fruitful method, you are asking the object that question in order to get its answer (the return value of the method).

This can help when designing classes as well. As you design a class and define its methods, think about whether each method is something you want an object of that type to do (implies it should be a void method) or a question the rest of the program might need to ask that object (suggests a fruitful method with a return value).